Youth Music, generational conflict, and the politics of time

Guillaume Heuguet

01/07/2023

“In every repressive society, the gap between generations is a powerful weapon for social control.”

Audre Lorde, "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference" (1980)

To put what follows into context, I am 34 years old and I have just started my first permanent job. Lately I've been torn between two sympathies. On the one hand, my sympathy for the ideas of the cultural and music critics I publish with Audimat éditions, such as Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds, and my students. Reynolds and Fisher are "popular modernists", they have maintained the defence of a variant of countercultural politics and aesthetics in the midst of the lasting power of right-wing movements, neoliberal as well as reactionary, mainly in the context of the UK and the UE. This can be seen in texts such as "Dance music : the end of the future" (published in French in Audimat n°0), for Reynolds; and in much of Fisher's work, but especially in his recent courses published as Postcapitalist Desire: The Final Lectures1 , where his reconciliation with the historical counter-cultural ideal is explicit. On the other hand, I have noticed in conversations with my students, but also with fellow writers of a younger generation, that they sometimes share a skepticism about countercultural politics/aesthetics. At the risk of caricaturing informal conversations I have had, they suggest, even if they don't make it into an argument per se, that it sometimes manifests itself as a typical discourse of intellectuals from a generation – the boomers – who have chosen their precariousness as a lifestyle and does not really suffer from it, which makes them hypocritical; that these politics are somehow outdated and unrelated to our current moment; that they are rooted in a mythological rewriting of cultural history that erases complicity or interdependence with mainstream politics and aesthetics; and that they are somehow counterproductive in that they prevent them from achieving their own autonomy, in the most material as well as the most symbolic sense: to speak and act for themselves.

My aim here is not to put the whole of the counterculture on trial, although I think it might still be an urgent task to make a clear-headed assessment of the arguments on both sides (in a way this is what Fisher tries to do in Postcapitalist Desire). I just want to reflect on the "generational" aspect of such arguments and their relationship to music and current politics. This invitation prompted me to think a little more about the current discourse pitting so-called Boomers (described as born between the mid-40s and 64) against Gen Z (born between the late 90s and 2010). I want to look at how it plays out in music and how it relates to politics, autonomy and attitudes to the future. I ask myself the following questions, although I will only sketch out possible answers: where does the prejudice that equates popular music with youth music come from? How did the autonomy of popular music as youth music turn into an open generational conflict? Why does everyone hate the boomers (even themselves)? Are retromania and hauntology (two crucial concepts forged in Reynold’s and Fisher’s writings on popular music) Boomer discourses? Has today's youth forgotten the countercultural past, is there a future for music and politics without generational conflict, and should our responsibility for the future matter at all?

Popular music as intergenerational coproduction, counter-culture as intergenerational conflict

Generational conflict is a constant in popular music. Popular music shapes our knowledge and emotions, it translates and forms "structure of feelings"2 and gives forms to "intimate publics"3 . In doing so, popular music shapes generational cultures and the differentiation of life stages. I would like to revisit this construction of popular music's relationship to generations. I want to ask whether the conflict between generations is inevitable. At a time when we are struggling against pension reform in France, I want to see if we can find emotional and intellectual resources in music to help us think about forms of intergenerational solidarity.

Generational conflicts in popular music are sometimes orchestrated by people who are not so far apart in terms of generation, as in the debate between rockism and poptimism. The stakes of this debate were summed up by The New York Times journalist Kelefah Sanneh (born in 1976) when he asserted the conservative character of the "old guard" of rock (including punk), which he accused of rockism:

A rockist isn't just someone who loves rock'n'roll, who goes on and on about Bruce Springsteen, who champions ragged-voiced singer-songwriters no one has ever heard of. A rockist is someone who reduces rock'n'roll to a caricature, then uses that caricature as a weapon. Rockism means idolizing the authentic old legend (or underground hero) while mocking the latest pop star ; lionizing punk while barely tolerating disco; loving the live show and hating the music video; extolling the growling performer while hating the lip-syncher4 .

The same kind of generational conflict can be found at the beginning of the techno scene in France, for example in the first issue of the French fanzine eDEN as early as 1992, when its authors denounced the archaism of the French discotheque scene. They found that the scene was unable to make room for the new generation in house music:

House music is the expression of a generation of individuals who identify with rhythm, parties, dance and the fusion of genres. A generation on the verge of frustration if the police and the club and venue owners conspire to break our momentum. Between the exorbitant prices of venue rentals, the archaic nature of clubs and the techno decay of raves, people who appreciate house music as a whole just have to stay home. No, we want to get off the beaten track and we'll get there in the end5 .

In 2015, a conflict appeared in the relationship between pop and club music, with the integration of mainstream cues and Eurodance sounds in "deconstructed club music" and underground spaces (think Total Freedom’s edit mixing Sami Baha and Rihanna's "Bitch Better Have My Money"6 or Venus X mixes7 ). It is still very much present today in the clash between straight techno purists and more queer friendly club scenes.

At other times, the generational conflict appears as an extension of an aesthetic but also ethical conflict, as with the myth of the golden age of rap. The question of rap's golden age crystallized in the mid-1990s8 ; the generation conflict is a classic feature of hip-hop and has played out with the arrival of the Dirty South sound, the Diplomats in New York, trap rap, mumble rap, until this year with plug and the so-called "New Gen" in France.

Despite these generational conflicts, there is no reason to reduce popular music to an expression of youth. When Ian Curtis, at 23 years old, sung "I remember when we were young" with a white voice which sounded like cooled by age, or when Youth Group covers Alphaville for "Forever Young" on the soundtrack of the TV show The OC9 , popular music's youth appears always already aware of itself, always torn between immediate nostalgia and a feeling of untimeliness. Popular music does not necessarily express youth as innocence. It prefers a reflexive approach to youth.

So where does the prejudice come from that popular music is the music of young people or for young people? Jon Savage tells us that in the post-war United States, a young female audience of fans of Rudolph Valentino or Frank Sinatra emerged10 . In the same period, there was a growing fear of delinquency among fourteen to eighteen-year-old girls, represented in films like Mark Robson’s Youth Runs Wild (1944). In this context, young girls and not-so-young male politicians set up the first “Teen canteens” to keep young people out of trouble. Teen canteens combining a dance floor, a jukebox and a Coca-Cola machine quickly spread to every region of the US. Seventeen magazine promoted dance crazes, fashion looks and outlined the new teenage market. With this specialization of places and media, the autonomy of youth pop music was produced by an alliance between generations. Together, teenagers and adults built not only a physical space but also a symbolic space for teenagers. This space was situated somewhere between the desire for autonomy of a specific age group, control by public authorities and commercial opportunism. This configuration has not changed much.

But how did this initial relative autonomy of popular music as/of youth turn into conflict? With his portrait of the young cultural bourgeoisie in his bestseller Growing up absurd (1960), Paul Goodman established the historical markers of youth as refusal. Goodman describes how a large proportion of young professionals walked out of their managerial jobs, young graduates walked out of universities and young soldiers walked out of the army. They abandoned the rat race and most institutions of control. Identifying with the working class and the black and Puerto Rican poor, part of this generation built a beatnik culture around a number of common traits: exteriority from society, "giving up the burden of explaining to those who often literally don't speak the same language"11 , fear of the cops, economic and professional uselessness, and perhaps most of all, their refusal to carry the symbolic burden of the future.

This position of refusal was turned into a more constructive one by members of the Youth International Party, formed in 1967 around Abbie and Anita Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Nancy Kurshan and Paul Krassner, recently recalled in Aaron Sorkin's film The Chicago Seven (2020), where they stand trial alongside their fellow protester, Black Panther founder Bobby Seale. The Yippies were actively working to organize a different future – anti-war and libertarian – and they were severely repressed. The counterculture's opposition to the "parent culture"12 is a generational, anti-institutional13 and enlightened – pre-"woke"? – rupture or shift14 . Music plays a key role: for conservatives such as Allan Bloom, through rock, youth defies the control of society, the family, the university15 , while for its proponents like Barbara Ehrenreich, “rock became, in the mid-1960s, the rallying point for an alternative culture, completely removed from the dominant structures, government, business...”16 .

In his 2012 critique of the concept of counterculture, Andy Bennett is quite harsh on the very notion17 . He insists that most of the time the term is used to describe a division within the narrow group of the young white bourgeoisie. Bennett criticizes the countercultural narrative for focusing on white and bourgeois groups to the detriment of a more open concept of the culture of this particular generation, which would encompass more diverse political interests (civil rights of various racial minorities, prisoners, gays and lesbians, ecologists, etc.). According to him, the reality of countercultural practices remains consumerist and does not always have an openly anti-capitalist position : for example, Woodstock only became free for all when its organizers were forced to let everyone in. "Counterculture" as a label is relevant insofar as it articulates the link between cultural struggle and youth in everyday life and perhaps for the first time on an international scale, but the term is often used to superficially weld together a wide variety of lifestyles and situations, often around music.

Rather than dismissing counterculture altogether, I think we should reclaim what is being left out: if the Rolling Stones both idealizes and transforms black rebellious attitudes to express a notion of youthful angst, it does not mean that we should not be interested in the contributions of black panthers or what Robin D.G Kelley coined as race rebels to notions of counter-culture; and we can always revise history by stressing the importance of the work of feminist groups in raising consciousness in anti-authoritarian ideology18 .

I do not think we can disqualify the counterculture as a simple petty bourgeois symptom: the counterculture was, and perhaps still is, an articulation between social struggles, lifestyles and the politicization of music in a field of multiple contradictory forces. After all, on the other side of the political spectrum, the cultural right has been prompt to set up an offensive reshaping youth culture into a very different, more conservative model. This happened in the United Kingdom with the magazines Fabolous 208 and Rave (1964), and in France with Salut les copains (1962), which promoted light "yéyé" rockers like Eddy Mitchell or Johnny Halliday, the values of the heterosexual couple, or the figure of the young dynamic manager. Let's also not forget what happened in France after Mitterrand's election in 1981, when youth became a political target-population through a public cultural policy with subsidized public music venues like MJCs (Maison de la Culture et des Jeunes - Culture and Youth Center) and SMACs (Scènes de musiques actuelles - Scene of current music), at a time when a series of books were putting forward the idea that rock music was not only consumed by mostly young people, but youth music in spirit: Edgar Morin19 , Jean-Charles Lagrée20 , Anne-Marie Green21 ... Even if it had its emancipatory aspects, this was also a way of managing young people so that they didn't become an unruly force, "ingouvernables".

Boomer's hegemony and the Gen X rift

If we follow the previous warnings to take a sober standpoint on popular music and counter-culture, we have to reckon with the fact that the baby boomers, born between the mid-40s and 1964, shaped the world of rock and pop as well as their association with youth. Even if the musical currents have changed, their cultural imprint has dominated the landscape ever since.

The boomer experience was born out of the crisis that resulted from the gap between the promises they received and the reality of the places that awaited them22 . In response, boomers have managed to perpetuate their frustration with this transitional experience. Until today, boomers tend to adopt two attitudes: either they assert that youth culture must age at their own pace, or that they themselves have remained young, unlike today's youth, who they feel do not manage to be young enough (they are too wise too early, etc.). In this second scenario, youth is no longer correlated to an age range (even if vague and changing) or to a material situation (not being a parent, not having professional responsibilities, etc.), but to a state of mind, a projection which makes it possible for the boomers to reject their own adult identity.

According to Grossberg, this boomer "state of mind" "erases the generations that could legitimately claim that youth" by heroizing their own (see the fetishizing of Lou Reed or Patti Smith early life stories). It is also intertwined with social institutions and prevents other social configurations from happening. (We might add that even if that is not always the case, they often turn youth into something to be talked about and spoken for. Much like in Foucault's idea of sexuality, youth allows for a series of strategies and desires: not only counterculture, but also with idol and Lolita culture, exciting TikTok revelations and gangs of hooded teenagers recording Chicago drill).

For Grossberg, it is because some boomers did not experience youth because of the war that they have been overinvested in youth: the idea of youth provides boomers with a retrospective identity, an anchor for a robust sense of self (we could call this critique a critique of boomer fragility). Grossberg also sees the open structure of youth as an ideal vehicle for the American national identity in crisis at this time of post-war reconstruction:

The [baby boom] generations (...) had the desire to relive a past they know they never had, in which their youth would have been smooth and somehow guaranteed for life. (...) Not only was [America's] youth identified with the perpetual youth of the nation, but its generational identity was built around its necessary and permanent youth23 .

Following Grossberg, we can say that heroic images of countercultural and musical resistance serve a psychic defense and fantasy against otherness. In this sense, the use of these images is as likely to be as conservative as other clichés and other stereotypes of images of a pro-family, pro-American imperial golden age. Grossberg's position eventually reached mainstream musical and cultural media, as exemplified by Luke Turner in The Quietus in 2013:

The myth of the Golden Age is beginning to lose its luster. The last decade has seen an explosion of music of vastly different genres, forms, volumes, sounds, aesthetics, origins, shapes, and sizes. In the age of fragmentation, invention is found at the extremes, not in the middle. Baby boomers confuse the absence of a central cultural narrative with a lack of progress. (...) It's ridiculous that a 20- or 30-year period in just two countries nearly half a century ago has been allowed to totally dominate conversations about contemporary music since then24 .

A few months ago, in an article for The New Yorker entitled "The 'Dazed and Confused' Generation" – a reference to Richard Linklater well-known movie from 1993 – Bruce Handy defended a simple idea: "People my age are called baby boomers, but our experience demands a very different label." He elaborates:

We grew up in the background noise of the previous decade, when youth was supposedly more exciting in every way: the music, the drugs, the clothes, the sense of discovery and possibility of change, the sense that being young was important (...) These days, baby boomer resentment is usually attributed to Generation X and millennials, but the ones who had to put up with the older boomers in the first place were their younger siblings (...) We don't need to mythologize ourselves. We don't even want to25 .

While Billy Idol and Douglas Coupland had dubbed it Generation X, Candi Strecker defended the same distinction. With another classic movie reference, her zines spoke of a Repo Man generation:

Those born in the late 1950s and 1960s...were now ignored. ... Those of us born around 1955 found ourselves at the hinge of two great movements [of the Baby Boom generation]: the hedonistic, drug-addled iconoclasm of the 1960s and the unbridled pursuit of materialism in the 1980s of the yuppie generation26 .

Why is this Gen X / Boomer divide important for music and intergenerational conflict? In the 1990s, Simon Reynolds and Mark Fisher, among others, embodied a relationship to music that could be called "popular modernism". They defended "hardcore" music, techno and jungle in the same way that their elders had embraced punk. Almost twenty years later, in 2012, Reynolds published Retromania27 . His diagnosis of the fate of modern music as incapable of true novelty was shared by Mark Fisher in his 2014 book Ghosts of My Life28 . He saw Arctic Monkeys as a symptom of capitalist realism. At this point, both Reynolds and Fisher were less interested in brutal and disruptive music than in the “futures of the past” that “haunt” the music of artists like The Caretaker, Burial or Mordant Music.

Simon Reynolds was born in June 1963. Mark Fisher was born in July 1968. Both are more or less members of this Generation X, lost between the counter-culture utopia of the baby boomers and the careless yuppies of the eighties. We can therefore interpret their criticism of "Retromania", of what Fisher calls the "slow cancellation of the future" via "capitalist realism" as a critique of the generation that preceded them. We can also read their interest in hauntology as a melancholic expression of this in-betweenness, a paradoxical attachment to the countercultural ideal that they couldn't inherit in practice. Ultimately, my hypothesis is that their interest in hauntology negotiates between a rejection of the myth of counterculture and an attempt to reclaim part of it.

In this, their attitude is consistent with another attachment they share, an attachment to post-punk. Post-punk no longer believes in the ideal of authenticity. Post-punk and New Wave people witnessed the limits, contradictions and betrayals of punk. They didn't give up, but they opted for a kind of strategic and political irony: by embracing their own inauthenticity, they hoped to intervene productively in the dominant cultural politics. But despite all this, the risk of self-fetishism for one's own culture and background is never far away in the discourse of hauntology. On the one hand, a mourning for lost futures resists a naive modernism that would too easily melt into consumerism, innovation, fashion and staged protest; but at the same time, the examples Fisher and Reynolds choose are inscribed in their own experiences in their mid-to-late twenties: raves, sci-fi TV shows on the BBC. It is already becoming a new canon that everyone in that generation is referring to, especially in the visual arts. I do not think these specific references are the most interesting part of their thinking. One can interpret the emergence of vaporwave, its relationship to eighties popular culture and its cascading differentiations – especially in the high-tech gothic laments of the Mallsoft genre (think Macintosh+ and the Orange Milk label...) – as an intervention that avoided this problem of canonization by shifting the decade. This removed the pitfall of vintage retrofuturism, but it also ran into the problem of ironic deconstruction becoming an end in itself.

From conflict to gap: 90s revival, youth/class and the struggle against the French pension reform

The revival of the 1980s, in varpowave and elsewhere, is an ironic and reflexive operation. The 1990s revival tends to play with a kind of revisionist innocence. The new generation seems to be using, willingly or not, the tropes of the 90s while discarding some of the real, material, social experiences consecrated by the musical culture of the 90s. In a conversation with Philippe Azoury during the symposium29 , we recalled what we perceived as the morbid ennui and darkness of the 90s: the depression of the suburbs and shopping malls, the effects of crack and heroin, ambient machismo, and so on. You could even hear them in mainstream power-pop hits like New Radicals' "You Get What You Give" (a tune that recently resurfaced with Joe Biden's presidential inauguration).

I think that when young people or older people use 90s codes today, they are mostly "playing" with style, using it as a space of nostalgia or a space of invention, but they are far from the question of cultural heritage, as stressed by Dan Dipiero:

Bands such as Soccer Mommy, Snail Mail and beabadobee, in particular, cultivate a genuine interest in the music of the 1990s (among others) and their listening habits influence their approach to sound both compositionally and productionally. This process could be described, however problematically, as an 'organic' expression of nostalgia rather than a conscious use of it30 .

In a way, this relationship between musical generations tends towards a rift rather than a conflict, a radical discontinuity: the same grounds are revisited and reinvented from positions that have become very different from each other. An illustration of this phenomenon can be found in Wiki/aesthetics31 , a project originally set up by a 21-year-old British student named Ella and influenced by Tavi Gevinson's trendsetting teen media magazine Rookie. There, musical subcultures and their original generational values seem largely subsumed by other aesthetic preoccupations, sometimes reduced to codes without depth, with whole decades seemingly dismantled and disinvested (the 60s, 70s, 80s are empty in the site's general chronology). I would argue that this subcultural mix functioning as a quasi-moodboard is not just a deprivation of historical reflexivity or a kind of postmodern take, as we have seen played out in other fields, but an aesthetic/culture in itself, prefigured by the now-famous-again "indie sleaze" trend. It values the frontality of reference and the pleasure of combining hyper-connotative design blocks from past cultural moments to saturation: it has already reappeared in recent music videos, from Ariana Grande's "Thank You Next" to Olivia Rodrigo's "traitor". And despite this focus on the superficial composing of vibes, browsing through the Wiki/aesthetics Discord channel, I feel that there is a search for an aesthetic position that is coherent with an ethical standpoint – in the absence of a wider political project.

Is the active forgetting of history in the 90s revival the only way out of the pressure of the boomers, their power over the definition of youth? In the Anglo-Saxon countries (USA, UK, Australia), young people belonging to Generation Z (born at the beginning of the century) feel the effects of precariousness and/or poverty of the neoliberal model. In France, sociologist Camille Peugny shows that poverty develops through the youth, both on an economic level and through the unequal access to diplomas and their devaluation32 . At my own level, I have witnessed deep depression, mental health problems and suicidal tendencies among my younger peers and family, as well as long queues at food banks.

But age is still less important than class as a factor of poverty/precarity, and at the risk of contradicting this generational analysis, there is an increasing proportion of financial inheritance being transferred from parents to children: this helps the person who benefits from it to have a better life, even if it doesn't always allow for the idea of autonomy associated with adulthood (which, as Gisele Vienne said in the symposium, is always a mostly white, male, non-disabled adulthood33 ).

With meritocracy as the dominant ideology of both public institutions such as schools and the market, any situation in which we find ourselves dependent on others is interpreted as a failure. In this context, criticizing young people's relationship with music (because it is not rebellious enough or, on the contrary, too infantile), or more generally, allowing the bourgeoisie to consolidate this ideology and avoid solidarity with the poor among the young, also allows other categories of older people to negotiate their anxiety about the precariousness of their own work, the rarity of job offers in which they are forced to compete, or living on a minimum social wage. At the same time, in order to prevent younger people's alienation and rejection of their own social norms (for The Economist has spoken of "millennial socialism"), adults and older people construct their own narratives of reconciliation, as seen in TV music competitions or music commercials, in the pseudo-transgenerational complicity around the boomer repertoire on French national television, up to the recent obsession with young people discovering Kate Bush's "Running up that Hill" via Stranger Things and TikTok. Consciously or not, these attitudes obscure the violence of class relations.

The recent struggle in France against the pension reform is another area where age relations have been played out as class relations. At the beginning of the movement, some of the younger people around me refused to take part in the protests and to fight for a future social benefit, which they saw as a delayed demand for equality and justice, replacing a demand for immediate justice. I read this early mistrust as a rejection of the bourgeois and adult discourse that asks working-class youth, but also students, artists, researchers, to accept their current poverty or precariousness as a necessary ordeal before they become productive workers and as such deserving of adequate social benefits.

In this context, the French youth and their trade union representatives could have chosen to turn their backs completely on their elders and push for their own agenda of youth benefits (RSA Jeunes) or a student wage, both of which had been raised in public debates a few months earlier (with the result of a benevolent increase in grants for lower class students). Instead, they chose to fight within the movement against the pension reform, within the trade unions, autonomously or in the feminist and queer corteges, using their specific experience to go beyond their own political identity as "youth".

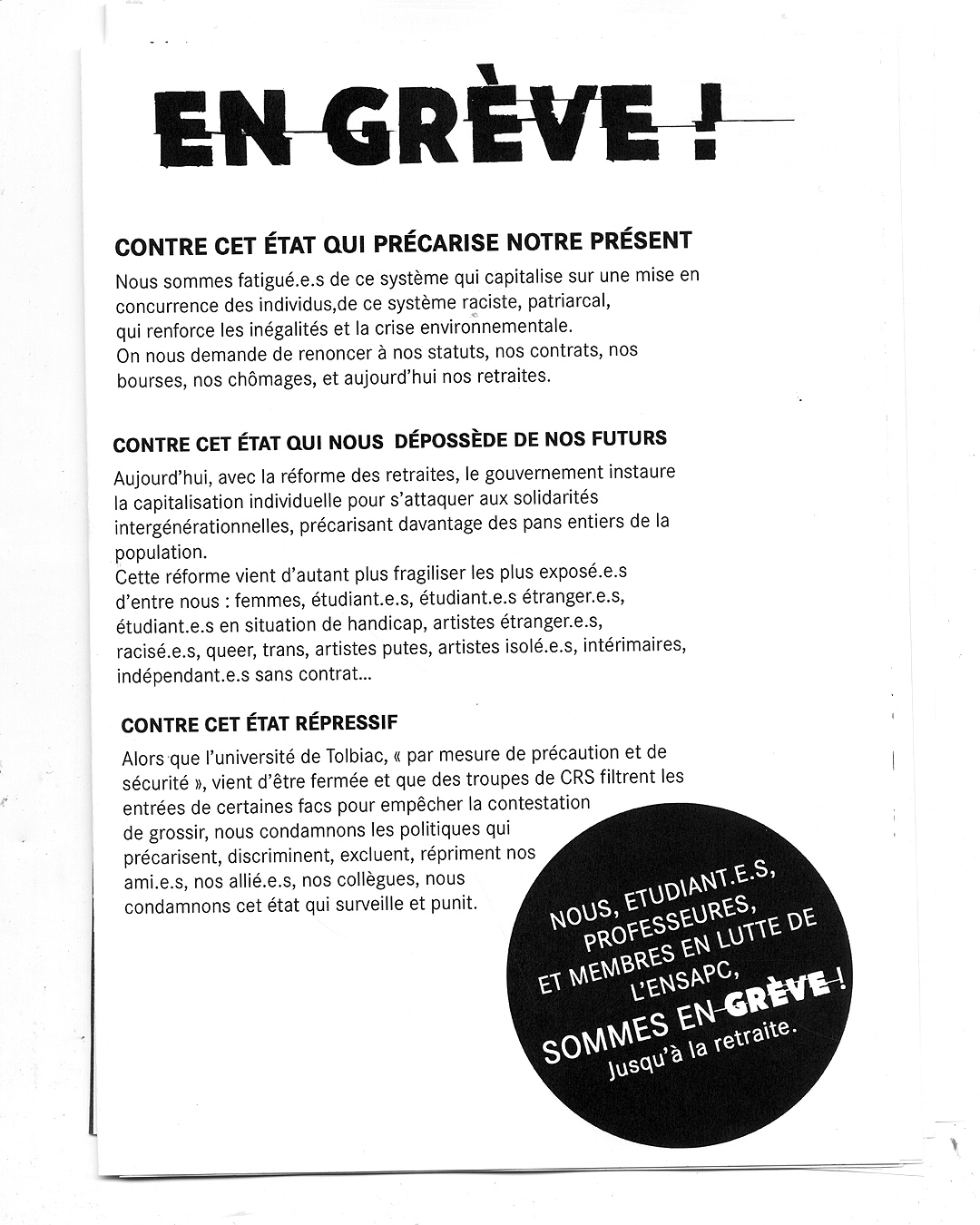

They thus contributed to the political line of the struggle in two ways. Firstly, by attacking the idea that one must be or have been non-dependent, autonomous and productive in order to deserve one's own economic survival, political autonomy or even a good life, thus challenging the centrality of labor and partly joining the positions of various currents of struggle, from the trade unions and political groups rallying the unemployed to the renewed vitality of the various organizations fighting for one or another continuity of wage in a discontinuity of employment contracts (CIP-IDF, Snap CGT, Réseau Salariat, La Buse, etc.) as well as more autonomous groups such as the collective responsible for Revue Show, an outshoot of the Beaux-Arts de Cergy, whose tract articulates the public pension system with the various subsidies for "social reproduction" threatened by the neoliberal reform (including student grants) and makes explicit a stand for intergenerational solidarity (private pensions, with individual capitalization/investment logics, contradicting the idea that with each generation, taxes on the profits of companies and the wages of the active population pay for the pensions of the elderly).

The youth engaged against the reform put forward a second major political standpoint: they refused to be victims of the part of the older generation's reducing them to an abstraction through their optimism or skepticism (“they will be the ones saving the planet”/”they are too lazy to build their own economic future, like we did”) as much as they refused the broader neoliberal mandate to invest in one's own future: they demanded immediate justice and reclaimed a right for the means to live a good life in the present. In many ways, this had even more resonance as an antagonism as it was the very right that the cultural bourgeoisie had in many ways already taken away from them. “Boomers” would be wise to understand this situation and escape both romanticizing youth and condemning young people in advance.

"On Strike! Against this state which precarizes our present / Against this state which deprives us of our futures / Against this repressive state – today with the pension reform, the governement sets up the individual capitalization to attack intergenerational solidarities (...)"">

"On Strike! Against this state which precarizes our present / Against this state which deprives us of our futures / Against this repressive state – today with the pension reform, the governement sets up the individual capitalization to attack intergenerational solidarities (...)"">

Tract from the pension reform movement by the "students, teachers and members in struggle of ENSAPC – on strike! until retirement".

"On Strike! Against this state which precarizes our present / Against this state which deprives us of our futures / Against this repressive state – today with the pension reform, the governement sets up the individual capitalization to attack intergenerational solidarities (...)"

Toward a musical politics of time

How can this political conjuncture and the political inclination of at least some young people towards intergenerational solidarity help us to read what is at stake in current popular music?

Despite partly class and partly generational inequalities, part of young people share a political interest in challenging the centrality of work for survival, and in maintaining a common solidarity and support for social reproduction. They may not be so much interested in rejecting ageing, they share a potential aesthetic inclination to make ageing funny, and to bend the ideological mandate to choose the future over the present or the present over the future, to blur that divide, and more generally to bend the experience of time in music.

It is already noticeable in parts of popular music that the musical expression of unproblematic youthfulness, in contrast to the now established "boomer" taste for the sign of newness as youthfulness, is no longer so much contemporary and exciting as such. There is probably something more symptomatic in the way Fever Ray, as an aging trans person, chooses to sing about passionate love and sex34 ; in Rae Sremmurd's strategic and playful anachronism with “Black Beatles” (2016) (the freezing of time in the subsequent Mannequin Challenge is no coincidence); in Lil Yachty's bridging of his regressive rap with pop psychedelia; in Pink Pantheress making hardcore/jungle cute and rejecting its masculine linear teleology based on the structure of build-up, break, drop in favor of a quick gratification that is cut off halfway through (as in “Break it off” (2021)); or in the high-speed techno/dance/trance sets broadcasted by Hör Berlin, which may feel like duplicates of previous dance music eras, but are distinct in that they are not built towards the experience of time liquidity that was a staple of club experiences in some earlier contexts, but toward short capsules containing full-on energy in a bounded time-frame/box.

Moreover, I have found that much of the most exciting music today directly or indirectly problematizes techniques of attention or the experience of duration, as if trying to intervene in the texture of time itself. The political economy I described earlier is associated with a number of different, contrasting experiences and affects that are played out in today's music, such as the pressure of the past (the musical legacy of the boomers as a burden under which youth is constantly buried and has to catch up), a temporal/rhythmic precarity (because you always have to keep up in order to find a homeostatic position in the unstable asset economy), or infinite delay. Hyperpop could be seen as a reaction to the pressures of the past, playing not only with tactical anachronism but with the excess of the past as a sea of waste; Footwork has been analyzed by Mark Fisher as a symptom of temporal precarity:

Novelty is to be found in the refusal of communicative capitalism’s false promises of smoothness. If the nineties were defined by the loop (the ‘good’ infinity of the seamlessly looped breakbeat, Goldie’s “Timeless”), then the 21st century is perhaps best captured in the ‘bad’ infinity of the animated GIF, with its stuttering, frustrated temporality, its eerie sense of being caught in a time-trap35 .

This is definitely a critics' take, and it does not account for much of the way Footwork is activated by the dancers in Chicago clubs, but then again, DJ Spinn has composed a track explicitly called “The future is now” (2015). The more interesting aspect of this, though, might be the infinite delay manifested in some of my favorite popular music of recent years, from Playboi Carti's very short, snippet-sounding song choruses (from "Magnolia" (2017) to "@meh" (2020)) to corecore videos and weird jersey club cuts (see, for example, qua's productions36 ). More broadly, these productions tend to defy any notion of musical progression and even of musical autonomy and productivity, of music as a thing whose production and use relate to an optimal use of work or leisure time, reclaiming the status of music as a technique for qualitative and reflexive modulation on the deeper experience of time and affect itself. This is not a Boomer thing, this is not a Gen Z thing, this is trying to find a way out.

The author would like to thank the students at MO.CO. Esba, including the Trash Press / Refusant·exs group, the students at ESACM – École supérieure d'art de Clermont Métropole, and Victor Dermenghem for some of the exchanges that inspired this essay.

- Mark Fisher, Matt Coquhoun (ed.), Postcapitalist Desire: The Final Lectures (Repeater, 2021) ↩

- Cf. Raymond Williams, Michael Orrom, Preface to Film (Michigan University Press, 1954) ↩

- Cf. Lauren Berlant, The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship (Duke University Press, 1997) ↩

- Kelefa Sanneh, "The rap against rockism." The New York Times, Oct. 31st, 2004. ↩

- http://christophemonier.free.fr/eDEN/Presentations.htm ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CjaLps_E3dc ↩

- https://soundcloud.com/ghe20g0th1kradio/venus-asmara-putaria-maxima-volume-1 ↩

- Laurent Fintoni, "Le hip-hop nineties ou l'illusion du sacré", Audimat n°5, 2016 ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WynqKFGQIXU ↩

- Cf. Jon Savage, Teenage (Faber & Faber, 2021) ↩

- Paul Goodman, Growing Up Absurd (Random House, 1960) ↩

- Which is in fact dialectical mix of differentiation and homology. The Birmingham Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies emerged as a way to make sense of youth culture relationship to both what they call "parent culture" and the mainstream. Cf. Stuart Hall and Tony Jefferson (eds.), Resistance through rituals (1975) (Routledge, 2006) ↩

- The concept of "counter-culture is sometimes attributed to the professor Roszak sympathetic analysis of the late-sixties conjuncture and generalizations from the observation of the lifestyles of his students. Cf. Theodor Roszak, Towards a Counterculture, (Doubleday, 1969) ↩

- Most genealogies of the semantics of "woke" and "wokeness" rightfully emphasize several africain-american and anti-oppressive groundings, but we can also link its wider meanings back to the comments on libertarian sensitivity and enlightenment among the politicized youth in Charles A. Reich descriptions of "Consciousness III". Cf. Charles A. Reich, The Greening of America (Random House, 1971) ↩

- Cf. Alan Bloom, « La musique et l'âme des jeunes », Commentaire, (No. 37, 1987/1), p. 5-14. ↩

- Barbara Ehrenreich, Dancing in the streets: A history of collective joy (Macmillan, 2007) ↩

- Andy Bennett, "Pour une réévaluation du concept de contre-culture." Volume! 9 (2012): 19-31 ↩

- Mark Fisher talks about this and Ellen Willis' contribution to this movement in Postcapitalist desire: see "Lecture Two: “A Social and Psychic Revolution of Almost Inconceivable Magnitude”: Countercultural Bohemia as Prefiguration", in Postcapitalist Desire (Repeater, 2020) ↩

- L'esprit du temps. Essai sur la culture de masse (Grasset-Fasquelle, 1962) ↩

- Les jeunes chantent leurs cultures (L'Harmattan, 1985) ↩

- Anne-Marie Green et al., "Jeunes et musique", Jeunesse et société n°10, février 1988 ↩

- Lawrence Grossberg, "Rock and youth" in We gotta get out of this place (Routledge, 2014) ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Luke Turner, "How The Baby Boomers Stole Music With Myths Of A Golden Age", thequietus.com, October 3rd, 2013 ↩

- Bruce Handy, "The 'Dazed and Confused' Generation", March 2nd, 2023 ↩

- IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFESTYLE; A Seventies Flashback Part One (zine), 1990 ↩

- Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction to Its Own Past, Faber & Faber, 2012 ↩

- Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Zero Books, 2014 ↩

- https://theravingage.com/programme ↩

- Dan Dipiero, "Around Again : nostalgie dans la musique populaire", Audimat n°17, 2022 ↩

- https://aesthetics.fandom.com/wiki/Aesthetics_Wiki ↩

- Jean Bastien, "Entretien avec Camille Peugny : Pour une politique de la jeunesse", Non Fiction, February 9th 2022 ↩

- https://theravingage.com/programme ↩

- Chal Ravens, "Fever Ray’s Karin Dreijer on romance, ageing and kink: ‘There is always the dangerous route’", The Guardian, February 17th 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2023/feb/17/fever-ray-karin-dreijer-romance-ageing-kink-dangerous-route ↩

- Mark Fisher, "Break It Down: Mark Fisher on DJ Rashad’s Double Cup", Electronic Beats, October 22, 2013. https://www.electronicbeats.net/mark-fisher-on-dj-rashads-double-cup/. ↩

- https://soundcloud.com/0ooqua/ultimate-ninja-storm-3-qua-x ↩

Guillaume Heuguet holds a PhD in media studies from Sorbonne University. He works in France as a professor of art history and contemporary art at ESACM and as a publisher at Audimat Éditions. He founded the music label In Paradisum, the magazine of musical and social criticism Audimat and the magazine of technological criticism Tèque. His research work focuses on media technologies, popular music and the relationship between aesthetics and politics. He is the author of YouTube et les métamorphoses de la musique (INA / Bloomsbury), the reader Penser les musiques populaires (La Rue Musicale, with Gérôme Guibert) and has edited the collections Trap (Éditions Divergences / Audimat) and Chill (Audimat).