Younger Than You

Federico Campagna

01/06/2023

In this short essay, I will discuss the metaphysical aspects of youth, its relationship with practices of world-building and the connections between youth, the end of the world, and forms extra-cosmic solidarity.

Metaphysics of Time and World

The notion of youth is composed of two essential elements: time and energy. Time, because it is a specific age. Energy, because it is associated with a moment in life, which is typically blessed (or cursed) by an abundance of energy.

To explore the notion of youth, let us begin by looking at the idea of time.

Time is a central theme in metaphysics, and it features among the fundamental structures of our experience of reality. And yet, even though time feels so close to us to the point of enveloping us, as soon as we look at its notion we realise that there are some very big problems. As Saint Augustine remarked, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know: if I wish to explain it to one that asks, I know not.”1

Time has struck many philosophers over the ages as a notion that is problematic, if not downright wrong. In the 5th century BC, the Eleatic school disproved the passing of time as a logical impossibility. In the 3rd century BC, the Indian Theravada Buddhists defined it a phenomenon that is entirely mind-dependant. In the 5th century AD, the Algerian theologian Saint Augustine describes it as a subjective parameter, dependent on our consciousness. In the 19th century, the French mathematician Henri Poincaré called it as a mere convention, while the English philosopher Francis Herbert Bradley defines it as an apparent but inconsistent notion. In the 20th century, the English metaphysician John McTaggart used logic to demonstrate ‘the unreality of time’, while the Austrian mathematician Kurt Gödel defines time as something devoid of real existence. Today, quantum physicists have added their voice to destabilize further any fixed or ‘real’ notion of time.

And yet, time continues to remain present to our experience. How can this be?

This paradox is perhaps best expressed by the definition of time that Aristotle provides in his Physics: the “counting of change with respect to the before and after.”

According to this definition, time is a way of keeping track (“counting”) of the changing events, which depends entirely on how this “counting” is done. But time is not only relative to the many possible ways of “counting” the changing events. It is also relative to which events are considered by this “counting”. Indeed, there are infinite events taking place at every instant within reality. We are able to perceive only a small range of these events, depending on our biological limitations, our social influences, our personal preference and inclinations. The specific selection of events that we are able, or willing, to recognize, counts as our particular “world”, which we extract from the great chaos of reality. Our particular way of counting these events, counts as our specific “time”.

We are beginning to see how some of the notions that we usually take for granted, are actually neither natural nor stable nor universal. Things such as “time” or “the world” (and I mean this world, around us right now) are artificial things, created by us, and they depend on us for the way they appear. This also means that different people, and different creatures, experience time and the world in different ways. All creatures that have an awareness towards reality are similar to each other, in their being points of consciousness, but each of them live inside different worlds and different times. This is what Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, building on Amazonian metaphysics, calls “multinaturalism”2 .

We have countless examples of how different groups or individuals inhabit different times and different worlds. Among the most recent, we can consider the 2013 court case in which a mining company was found guilty of desecrating the Australian Aboriginal sacred site called Two Women Sitting. The company was fined for desecration, but the Aboriginal people had asked a sentence for murder: the fundamental problem, of course, was their different metaphysical construction of the world.

Youth as Time, Youth as Energy

But what does all this have to do with the question of youth?

Firstly, it tells us that youth, as a measure of time, is intimately related to the very stuff that makes up our distinct worlds – and thus to their same fundamental unreality. Secondly, it tells us that the concept of youth is entirely relative, and that there is nothing “natural” corresponding to it. Youth is not a denotative term (i.e. it doesn’t explicitly describe something objective), but it is connotative (i.e. it is a term whose real meaning is the particular emotions, feelings and expectations that are connected to it).

So, let us now move to consider the feelings and expectations that are attached to youth – which are connected to its second essential aspect: energy.

When we talk about expectations, we are always dealing with someone else’s desire. Even the expectations we have on ourselves are our way of interiorizing what we think are the expectations of other people (or of what Jacques Lacan used to call “The Big Other”).

The same goes for youth.

We can find a significant trace of the expectations attached to youth, even just by looking at the term itself. The etymology of youth, in the English as in the French “jeunesse” and in the Italian “giovinezza”, etc., comes originally from the Sanskrit Yuvan (strong), which in turn derives from Yavan (defender), which comes from the root Yu (to fight, to repel). So, the word for youth, as accepted in most European languages, is fundamentally connected to the meaning of “strong defender, strong fighter”.

With such a vague characterization, it is implicit that the object of this act of defending is everything: the young are those who are expected to dedicate their life to fighting, and possibly dying, to defend “the world” in its totality.

And yet, as we saw earlier, there is not only one world. Which world are the young actually expected to defend?

The clues are easy to find: as famously remarked by US president Herbert Hoover in 1944, “Older men declare war. But it is youth that must fight and die. And it is youth who must inherit the tribulation, the sorrow, and the triumphs that are the aftermath of war.” Today, governments are worried about the decline in birth-rate, because the young are needed to pay into the pension funds that support the old (since the rich old people are unwilling to share their wealth with poor old people). Since time immemorial, social institutions, from the prison to the army to education, have been geared towards channelling the energies of the young in order to stabilise and defend the world of the old.

Of course, the expectation that the young fight and die to defend the world of the old is preposterous to say the least. And yet, which other world should the young feel as their own, and dedicate their energies to protecting?

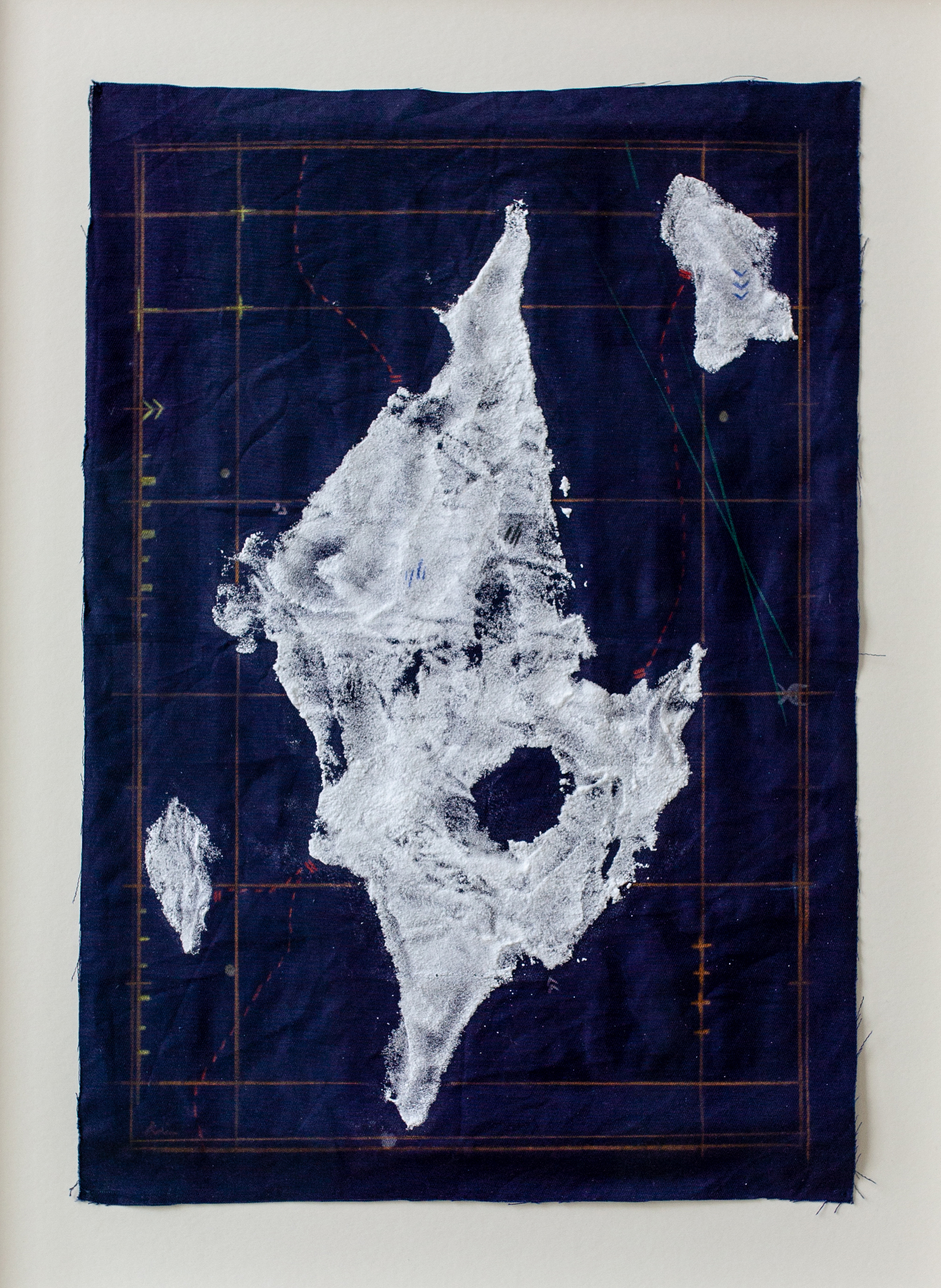

Rain Wu, The Sea Rises and Totally Still III-10 (2020). Fabric, seawater, chalk. 49x63cm. Courtesy of the artist.

An Individual World

Let me begin by clarifying that this question is not limited to those who are “young” in the sense that they were born just a few years ago: because the concept of “youth” is a relative concept that refers, not to time, but to the availability of energy and the willingness to defend a certain world. Thus, we could say that anyone, of any age, is “young” to the extent to which they are willing to able to use their energies to build and defend a particular world.

On this basis, it is possible to sketch a basic roadmap of how a young person might explore the different world to which they can dedicate their youth.

The journey should start, of course, on an individual basis. Every person should start by building, exploring and defending reality as it appears to them on the basis of their particular cosmogonic process. This is their private world, whose conformation depends on how they “read” reality, which events they select as real or unreal, how they decide to construct the metaphysics of their world, etc.

This focus on the individual is especially fruitful, because it opens each person to the experience of loneliness and fear: when one tries to “make world” on their own (i.e. to observe reality by themselves, and have a first experience of rebuilding a world), one begins to wonder “Am I going crazy? Is my world real?”

This experience of loneliness and fear has significant consequences. If one perseveres, one goes on to understand that all worlds are a form of “madness”, literally a hallucination, and that none of them is absolutely “real” or natural or stable. This realisation opens up a mystical horizon: the individual world-builder, beset by loneliness and fear, begins to realize that there are infinite possible worlds happening simultaneously, and that between and beyond them lies the “real” reality, wordless, timeless, beyond our comprehension and sunk in absolute silence. One realises the unreality of worlds and the unworldliness of reality: the relativity and mortality of all worlds.

Kinship Across Worlds

After this individual experience of worlding, one might want to ease the fear and loneliness by associating with other worlds. They might want to create relationships of kinship and solidarity between their private world and other worlds, created by other creatures. This is the true beginning of the “social contract”: the social contract is a mere fantasy, if applied to “society”, but it is a reality if it is applied to this wilful creation of a network of kinship between worlds. This network is precisely what the anarchist theorist Max Stirner called a “Union of Egoists”3 : a union that is not the consequence of a pre-existing bond (ethnic, cultural, racial, by class, religious, etc), but that is the product of a wilful, reciprocal choice.

This kinship does not have to take place within the immediate proximity of the individual. One can associate with, help and defend other worlds, created by other creatures very distant in culture, in race, in species, in space, and even in time. The young of today (both those who are young by birth, and those who are young to the extent of their cosmogonic energy), can choose to disentangle their “youth” (i.e. their cosmogonic energy) from the idea of world and reality that is hegemonic in their geographic vicinity and in their contemporary present, and associate instead with other creatures who have lived or will live in the past or in the future.

This is especially relevant today, at a historical turn in which worlds that used to be socially hegemonic are approaching the end of their historical course.

Rain Wu, The Sea Rises and Totally Still III-12 (2020). Fabric, seawater, chalk. 56x66cm. Courtesy of the artist.

How Worlds Die

It is normal for worlds to come and go. Not only the worlds of the individuals, but also the collective worlds of entire societies are destined to die – that is, the general idea that the “world” is made in a certain way, that “time” flows in a certain way, that certain events are real and others unreal, that certain things truly exist and others don’t.

These large collective worlds, which are endorsed by an entire social body for a long period of time, are typically called “civilisations”. Like individual worlds, they too come and go.

Today, it seems likely that the kind of world that has been promoted by the Western civilisation – and that has become hegemonic over large areas of the planet – might be nearing its natural end. The reasons for its demise are numerous, including its global cost in terms of the environmental and humanitarian crises which it has caused, and its complete dependence on a complex yet fragile network of technology, energy and supply. Furthermore, at present, history is going through a turbulent period of geopolitical conflict, which is significantly resizing the influence of Western powers.

The end of a world is always traumatic, as it happened at the end of Roman antiquity, or of the Mesoamerican civilisations. But passed the shock, the people who survive the catastrophe soon begin to work to construct a new world: not just a new society, but a new metaphysical “common sense” about how reality is structured.

Those who find themselves at the beginning of a new world, after the end of an old world, have a difficult task: literally re-creating metaphysics, almost from scratch. I said almost, because typically they look back at the ruins of the dead world, searching for something useful for their cosmogonic work.

Thus, Homer, in creating the epics that inaugurated the new Greek civilisation which followed the 500 years of the Hellenic Dark Ages, looked back for inspiration to the long-gone civilisations of the Mycenaeans and of the Minoans. Similarly, when Charlemagne pushed Europe outside of the darkest centuries of the early Middle Ages, he looked back at the long-vanished civilisation of Classical Roman antiquity.

By looking back, the creators of a new world open a channel of communication with world-builders from past eras. Through this same channel, today we can speak to the people that will come after the end of our world, after the end of our time, after the end of our future.

Who are these post-future people?

We know just a few things about them.

We know that their mission is difficult: they must try to make sense again of reality and to create a new mythology and anew cosmology.

We know that their form resembles that of adolescents, because adolescents are also people that come after the end of the world of childhood, before the establishment of the hegemonic world of adulthood. And that, like adolescents, they too are afraid of both “order” and “disorder”. They are aware that too much disorder means an unliveable chaos, and it must be tamed. But they are also aware that too much order would destroy freedom, and eventually would crush them.

And we also know that they often look at the past, seeking help and inspiration, and that they appropriate its legacy by misunderstanding it (as beautifully presented by Russell Hoban in his magisterial Riddley Walker 4 ). Those who will come after the end of our future, of our current “old” world, will look back towards us, seeking our help.

A Cosmological Legacy

To conclude these reflections, allow me to clarify that I believe that every person should be free to use their youth however they wish. A person can legitimately subscribe to the existing world-form that is currently hegemonic and fight to defend it. Or they can remain locked in their private world. They can associate in networks of cosmological kinship with their immediate neighbours in space and time. Or they can open their kinship to other cultures, groups or species or historical eras.

Personally, I would like to invite the reader to consider the possibility of directing their “youth” in view of those who will have to build a new world after the end of our own. I see it as a matter of “cosmological responsibility”, similar to the environmental responsibility that makes us think deeply about our legacy to those who will inhabit the natural environment after the end of our civilisation.

By opening up to the post-future adolescents, today’s young can avoid fighting and dying to defend the old, but they can instead provide a parental help to those even younger than them – so young that they are not even born yet.

This help is provided by leaving them a cultural legacy that speaks of how it is possible to reinvent the world, so to be helpful to those who will have to reinvent one without the support of a stable ideology of the world. It must be a legacy that tackles their fear of order and disorder, reassures them about the fragility of all worlds, and teaches them about the art of creating worlds.

It also means to embrace the openness of cultural communication, since the post-future adolescents will certainly misunderstand and pillage and badly appropriate whatever we will leave to them. They will treat our dead cultural legacy as the soil from which they can grow a new plant of the world.

Opening a network of kinship with post-future adolescents, and leaving to them ideas about the cosmos that they can use, means to truly transcend the contemporary idea of cultural production, and to revive in the most anarchic and thus authentic way the process of cultural tradition.

I would like to close with the words of Goethe, from the West-Eastern Divan: “It is still day, let us get up and going! The night, when none can work, is at the door.”5

- Saint Augustine, The Confessions, XI, 14. ↩

- Cf. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics (2009), trans. Peter Skafish (University of Minnesota Press, 2014) ↩

- Cf. Max Stirner, The Ego and Its Own (1844) (Cambridge University Press, 1995) ↩

- Cf. Russell Hoban, Riddley Walker (Jonathan Cape, 1980) ↩

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, West-Eastern Divan (Cotta Publishing House, 1819) ↩

Federico Campagna is an Italian philosopher based in London. His work focuses on the relationship between metaphysics, world-building and intellectual history. His latest books are Prophetic Culture: recreation for adolescents (2021) and Technic and Magic: the reconstruction of reality (2018). He is Associate Fellow at the Warburg Institute and Critical Fellow at the Royal Academy Schools in London. He is the co-founder of the Italian philosophy publisher Timeo and works at the UK/US radical publisher Verso.